A Conversation with Layla Khoshnoudi and Abby Rosebrock

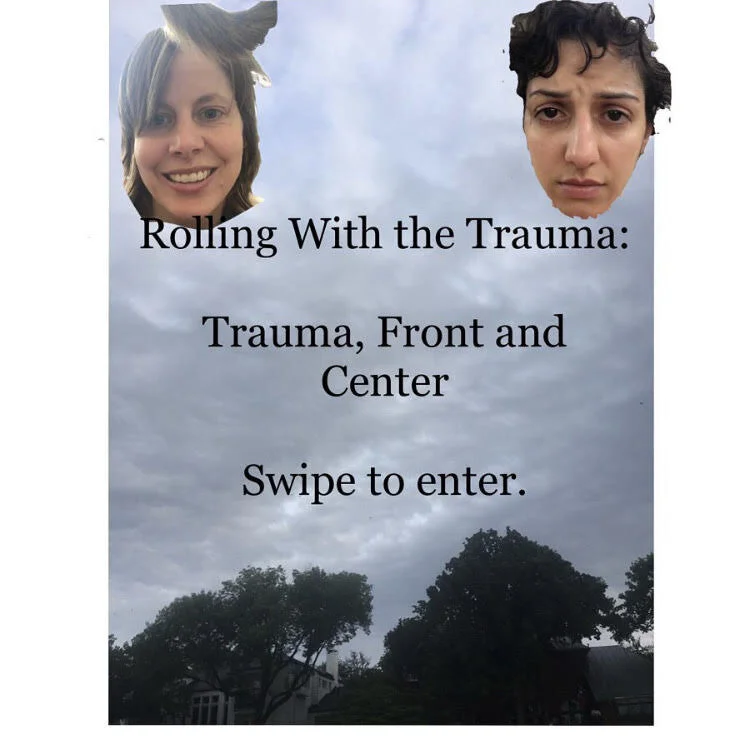

I recently discovered the nightly Instagram series from The Sactioned Radical Negativity Network, "Rolling with the Trauma: Trauma Front and Center." I was immediately taken by its singular energy. Created by Layla Khoshnoudi and Abby Rosebrock, the show contains comedy so deadpan, it might kill you. In a series of guffaw agnostic close-up videos, Khoshnoudi and Rosebrock explore attachment patterns, the new Fiona Apple album, back lighting, cutting one's own bangs and projecting, all through the prism of trauma. I emailed Khoshnoudi and Rosebrock some questions this week.

This first question is for Layla. What was your original thought behind the Fem. Queory Instagram account, which you started in September 2019?

Thank you so much for knowing that, and asking that. Ha. The name came out pretty impulsively, but it has sort of revealed itself with time, satisfyingly. What I wanted to do with Fem. Queory when I started it was be as thoughtless as possible, and just sort of release whatever bubbled up in the moments when I wanted to express something so badly, but didn't know why, and might have felt too self-conscious to in a space where people didn't freakin' ask for it, ya know what I mean?

And as it's accumulated, I see it largely as a space to be--sorry for the cliché, but--unapologetically female. Clearly I don't mean that to be as buzzy as it sounds, but I think there is a radically feminine quality to the content, which emerged in unexpected ways and feels audacious.

Like a lot of great art, I struggle for language to describe how I feel about "Rolling with the Trauma." I was looking for an easy way to explain the comedic angle of the show and I think the most striking entry point is that you both speak with great sincerity, rarely smiling. What was behind that choice?

Layla: Haha, amazing question. I think, for me, above all it was a reaction to the pressure to be positive. I don't really know where that pressure comes from but it's powerful. Capitalism, right? Damn, it's always capitalism. Anyway. I think I've valued positivity so much, and admired people that have their shit 'together' and wanted to be like them so much, that the pressure was mounting even more than I knew. But at the same time, I've known that that isn't me. What I wanted was the dark stuff to live alongside the joy and celebration. That seemed more possible than stuffing it down with forced, positive images. But I didn't know how to find my way out of that mind-frame. So, one day I sent Abby this idea for a show (which ended up being the first RWT video we posted) where I right off the bat was like, This is our show and I don't care what anyone thinks!! Obviously knowing that anyone who says that, clearly doesn't feel that way. And I knew Abby would get it right away, because that kind of delicate irony is something we both appreciate. We're lucky to have each other. The collaboration is so fluid it borders telepathy.

Abby: I feel so lucky. And I love the telepathy. Since we're both interested in psychic and emotional states, I think we're drawn to paradoxes and mysteries as they show up in our inner lives. It’s funny and disconcerting to me that the line between sincere self-expression and narcissism/attention-seeking/self-pity is so thin. The more honest you’re trying to be, the more frequently you probably lapse into that shadow side of self-reflection. Where the honesty, healing and sincerity become dark forces (that’s not to say wrong or bad forces, but they can be destructive, insufferable, brilliant and blind at the same time). That’s a painful dilemma but being able to laugh at it helps. I think plunging into this psychic space and disregarding the social pressure to regulate self-expression in a way that's attractive allows us to access more complicated emotional experiences than we're used to seeing.

The show always leaves me with things to think about, even as I'm not sure how seriously I should be taking certain things. Layla, for example, asks: "Who defines righteousness? And, for that matter, who defines youthful?" And then the camera pans to her legs. It made me think about how a transcript of the show would play much differently than the filmed version. How do you explore the limited visual tools at your disposal in the Instagram format?

Layla: The limitations of Instagram, and furthermore my limitations with technology, are kind of conveniently in keeping with the whole raw and exposed nature of it. With this premise it feels like there is still infinite room to explore, despite the limitations. Conceptually Instagram was the perfect place for us to put forth these extremely unpolished characters, because I think it's where a majority of normalcy-flexing happens, and thus a sort of numbing artifice. The show is trying to cut through that.

Abby: This isn’t about tools, but thinking about Instagram as a medium, I challenge myself to look as bad as I can. Not funny-bad, just haggard bad. And not even “body-positive, “ which I think is a tool for selling things, and asks us to look away from the grotesque. I mean resisting the deeply ingrained concern with appearances that's understandably become a kind of survival instinct for a lot of women (definitely for me). Some part of me is always screaming “If you look unappealing you’ll lose work and be left for dead and everyone will think you're a loser and a bad person!” There's something satanic in that voice. So I’m trying to ignore that voice rather than appease it.

How did you settle on the format for the show?

Layla: Well there's really just the basic premise, which is that we do our best to not try to be pleasing to anyone but ourselves, and that's pretty much the only hard rule. No set format. What's being presented is the streaming together of what we're each putting forward, according to where we each are.

Each day it builds unpredictably. To me, that's a part of the integrity of the approach; to formulate each episode as intuitively as possible. To go purely according to our feels, feels radical and worthy in itself. Plus, you know, once you start planning too much it's easy to find yourself back in the fake shit, the why-why-why, which is numbing again. For this show the relationship to time is very alive and even tense in some ways, and that's part of what's making it fun and helping us through this scary time.

Abby: And of course quarantine dictates the fact that we're never in a room together. I miss being in a room with Layla but the surprise of seeing her clips from Texas every day is exciting in its own way.

What are your thoughts on the relationship between trauma and humor?

Layla: I'd say there's a certain spiritual verve which connects them. Plainly though, humor is how I save myself from depression. And I think it's the same for Abby. That's another angle of the show, the idea that it's just for our own healing. In a way that is true. Although of course, we want people to connect to it, and us. That's the dizzying combination and sort of where the funny bone is. Abby called the show polytonal once, which I think traditionally refers to music, but feels quite right. It's like this tiny little place where we can still feel magic, despite everything, by allowing the wildness. A place where we force ourselves to be free from judgement. Not that I think judgement is a bad thing, it's just nice to have a respite!

Abby: Oh, man--what Layla said about trauma and humor sharing a spiritual verve--I feel that. But you take a lot of risks when you invite trauma and humor to coexist in your work. I'm always wondering how to shine a light on the atrocities of human nature while also making room for merriment, levity, relief--and that juxtaposition is almost always going to offend someone or turn off people who are attached to slick categories. Capitalism likes properties that are easily labeled. But that's neither life nor art, really. Life overwhelms and art startles. Trauma and humor are chemically commingled, baked into both.